Penniless, woefully obscure Douglas Coupland went on a tear last week in the New York Times’ subscriber-only online thing:

"Can/Lit is when the Canadian government pays you money to write about life in small towns and/or the immigrant experience," the man writes. "There is a grimness around CanLit — the same sort of grimness that occurs when beautiful young adults are forbidden to leave home and are forced to tend to aging and dying family members, when they are forbidden to lead their own lives."

The idea that there is a fading, irrelevant older generation holding back an army of youthful and exuberant and ambitious authors is one I used to rant about myself, before I actually started working in publishing and realized that it's only partly true.

Yes, there is a generation or two of CanLitistes who got their mouths on the teat of grants funding back in the Trudeau era and will not be pried from it . But, their tenacity in defending their own entitlement is a lesson that has been learned well by subsequent generations of Canadian writers. To continue with Coupland’s metaphor, most of those “beautiful young adults” are quite happily abandoning all their youthful privileges and are acting, dressing, thinking, and writing like their frail elders, with the inevitable loss of vitality that comes with taking up something second-hand.

Coupland seems completely oblivious to the fact that A) the Canada Council and its provincial and municipal counterparts have very little sway over what gets published and read in this country; and B) most big publishers spent the last ten years or so throwing stupid amounts of cash around in order to outdo their competitors in the acquisition of new writers. Look at the head-hunting that went on at the UBC Creative Writing department a few years ago. Did that experiment pan out as well as they'd hoped? Is our literature any less grim because of it? Of course not, because it is insane to look to first-time writers to sutain either a literature or a publishing industry. New writers have to spend time learning their shit, period, or they will find themselves at the mercy of the law of diminishing returns as they struggle to regain what everyone found so “fresh” in their first works, like a child who inadvertently says something that gets a laugh from his parents, then spends the next hour desperately trying less-and-less funny variations on it.

The real problem with Coupland’s rant, and many like it, is that it assumes some kind of systematic cultural conspiracy against fresh, youthfully ambitious writing. The truth is, there is, and has always been, a cultural conspiracy against youthfully ambitious writing. And so what? It’s a fact of life and a fact of culture, here and just about everywhere else in the world. Truly experimental or daring writers (as opposed to self-consciously hip writers like Coupland who fill their work with signifiers borrowed from magazines and cover their stock narratives with a bit of postmodern sauce, as Kingsley Amis would say) will always be marginal and marginalized. There is wiggle room – one or two break through the dry crust or mainstream expectations, or find themselves lionized late in their careers or even posthumously – but for the most part, the weird stay weird, the tough, tough. It's up to readers to do the work, not granting bodies, and up to smart critics to help them. (Not that someone like Coupland would ever see it as worth his precious time and his beautiful mind to actually engage CanLit on a consistent basis, through reviews or essays, rather than the occasional drive-by rant, free of all context.)

What is really lacking in Canadian literature is courage – the courage of writers to pursue a literary vision single-mindedly, oblivious to the potential rewards, financial and otherwise, the whims of arts-grant juries, and false dichotomies like urban vs rural, experimental vs mainstream, or young vs old.

For the morbidly curious, you can read a review I wrote of Douglas Coupland’s Terry Fox book here. Coupland’s usual condescending approach to ordinary, unhip lives (“Ooh, look what these charming and unself-conscious Canadians do in their homes!”) bugged me more than I let on in the review, but in the end not even he can smother the effect of seeing things like Fox’s false leg, or handwritten tallies of the kilometres run.

Tuesday, August 29, 2006

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

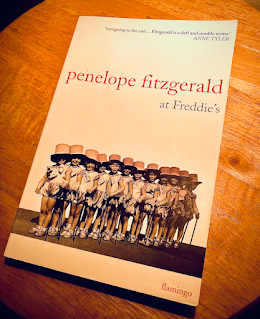

A very subtle and funny writer - one I've become obsessed with over the past year - in a decidedly Muriel Spark mood. Imagine The Pr...

-

Life is currently offline.

-

Mark Steyn is a dangerous idiot with a suspiciously homophobic streak for a bearded, show tunes-loving man who is drawn to big, strong, auth...

-

My review of André Alexis's Beauty & Sadness gets the full-page + cartoon treatment in the Toronto Star . A wee taste: It’s hard no...

5 comments:

Hey, Nathan. You're right, of course, that only the insane would try to sustain a literature with first-time writers. Problem being that today's cash-strapped publishers aren't likely to sign a writer to a second book if the first one doesn't meet expectations.

Jack McClelland used to say that he didn't publish books, he published authors. But most publishers today are so skittish and their financial situation is so precarious that they are reluctant to nurture an author through three or four books that underperform or don't find a wide audience. Once an author is dropped by a house, it becomes that much more difficult to find another house willing to take a chance on him or her.

The days of a house weathering the low sales of a Mordecai Richler in the early period of The Acrobats and The Incomparable Atuk, while allowing him to mature sufficiently as an artist to write The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and St. Urbain's Horseman, are largely a thing of the past. Similarly, few houses today will stick with a latter-day Timothy Findley while he publishes relatively obscure novels like The Butterfly Plague in the hopes that one day he'll have a breakthrough with The Wars. Which is too bad, because if a writer is allowed to mature to the extent that (s)he becomes a household name, that will have a beneficial effect on that writer's backlist and, by extension, the publisher's bottom line.

Clearly it was a mistake to throw stupid amounts of money at first novelists in the manner of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Publishers in Canada learned a hard lesson, and have become much more conservative and cautious in their publishing decisions as a result. This is probably a contributing factor to the grimness that Coupland sees in our literature.

But I think it's important not to allow the pendulum to swing too far the other way. New writers need to be nurtured and developed, and the only way this will happen is if they find publishers who believe in them and are willing to stick by them in the lean years, while they hone their craft.

The funding bodies are so watered down and spread so thinly that they can only provide enough coverage for the completion of mediocre works. Look at the number of poetry books published in Canada each year! It's absurd, and it is all financed by the granting bodies. The vast majority of contemporary fiction and poetry published in Canada is utter crap. The publishers have no idea what will or won't sell. And the reading public is laughably ignorant. What is really lacking in Canadian literature is talent, visionary publishers, and an educated readership.

Steven,

I agree that publishers need to nurture new writers (and if any big publisher wants to throw cash at me with no thought of returns, I am willing to be tempted), but what they did over the last decade was a kind of genteel, slow-motion version of what big record companies do in the search for the next Nirvana or Destiny's Child or whomever: scoop up everyone in a big net, throw around a lot of cash, treat all these newbies as the next big thing, then drop most of them when they inevitably don't fulfill expectations. No nurturing there.

By the way, I think Richler published his first novel with a UK publisher. His account of meeting his first Canadian publisher is quite funny - something along the lines of "How thick is this book? Because we tend to only publish thick books..." We're heading that way again.

If you read some of his letters, you'll see he was quite embarrassed and amused at the treatment he got in the Canadian press after publishing three novels - as if he were a major writer, when he knew it takes a lot more than that.

(Atuk came after Duddy Kravitz.)

Fuck. I knew I had the chronology wrong. I need to get me a fact checker. Unfortunately, no one is throwing big bucks at me, either, so I can't really afford one at this point. I suppose I could act as my own fact checker, but that just seems like so much work ...

I love the story Richler often told about people asking him what he wanted to do professionally, and when he'd respond that he wanted to be a novelist they'd inevitably follow up with, "Yes, but how do you intend to earn a living?"

The other problem with publishers searching for the "next big thing" is that they invariably base their search on the last big thing. Ann-Marie MacDonald had a hit with Fall on Your Knees? Let's find a whole whack of multigenerational family sagas by other writers, cuz they're sure to do just as well, since this is obviously what the public wants. It's the Pulp Fiction syndrome.

The fallacy being, of course, that one of the things that sold the public on the original work was the freshness and individuality of the voice. A hundred imitators of MacDonald or Tarantino will each come off like a photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy, and each subsequent iteration will be less and less interesting.

What's missing on the part of publishers, it seems to me, is courage. Not the courage to say, "We're going to give Author X a $30,000 advance, because that clearly signals that we think this book is a blockbuster." Rather, the courage to say, "Here's something fresh and new, from a unique perspective and an interesting voice that maybe hasn't been heard before." But this requires looking to the future, rather than the past.

It's a funny system we have. Impede the market by flooding it with subsidized work, and then complain when the market eventually catches up and rejects most of that work. Why not just let the market dictate from the start?

Post a Comment